September 27, 2010 - By John Sanford

Pressure sensors worn by various 49ers players in their uniforms are helping a team of Stanford researchers to measure the impact of blocks and tackles.

In collaboration with Newton’s laws of motion, most notably that one about force equaling mass times acceleration, the San Francisco 49ers are helping physicians and scientists at Stanford learn more about the biomechanics of football injuries

Daniel Garza, MD, an emergency and sports medicine physician at Stanford Hospital & Clinics and the 49ers’ medical director, is working with two research assistants to measure the impact of blocks and tackles using pressure sensors worn by some of the players in their uniforms.

“It’s unprecedented for an NFL team to support research at this level,” said Garza, an assistant professor of surgery.

Indeed, the project reflects what coaches and physicians with the 49ers describe as a unique and mutually beneficial relationship. Stanford Hospital, the only academic research hospital providing comprehensive medical care for an NFL team, knows a lot about treating athletes. (It has served as the official medical provider of Stanford Athletics for almost two decades.) Meanwhile, the 49ers are helping Stanford physicians advance the field of sports medicine.

“We have a population of elite athletes we can learn from,” said clinical professor Gary Fanton, MD, a Stanford orthopaedic surgeon and team physician for the 49ers. “We can collect biomechanical data to improve our understanding of sports health and sports-related injuries.”

William Maloney, MD, professor and chair of orthopaedic surgery and also a 49ers physician, emphasized that the knowledge gained from studying and treating the team can be applied beyond professional sports. “The benefit is that we can translate the care of high-level athletes to everyday athletes,” he said.

Forty-Niners co-owner John York, a retired clinical and research pathologist, supports the research efforts, Garza said. The NFL has also given its blessing, lifting the usual restrictions against computers on the sidelines so that Garza’s research assistants — Tyler Johnston, a second-year medical student at Stanford, and James Mattson, a 2010 Stanford graduate in human biology — can collect and analyze data.

“We’re trying to understand the biomechanics of the trauma players receive, so we can both assess how well their body armor is working and what physicians should be looking out for,” Garza said. He cited the example of former Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback Chris Simms, who ruptured his spleen during a 2006 game. Unaware of the gravity of the injury, Simms went on playing — a decision he later admitted could have cost him his life.

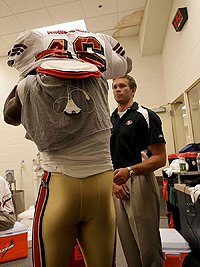

A player for the San Francisco 49ers puts on pads and impact sensors, as Tyler Johnston looks on.

“It’s difficult to assess these athletes on the sidelines when they’ve potentially sustained some kind of internal injury, especially when they’re reluctant to leave the game,” Garza said.

With this in mind, Garza launched the sensor project, funded by the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, about two years ago. Sensors are worn on the chest and abdomen of some offensive players and in the shoulder pads of some defensive players. The players also wear wireless transmitters, which send information about the force and location of hits to laptop computers on the sidelines.

The researchers hope the data they collect will teach them more about the incidence of chest, abdominal and shoulder injuries in the sport. Eventually, their work could lead to advancements in protective gear and earlier diagnoses.

At the same time, Garza, Johnston and Mattson are conducting a second experiment, using infrared cameras to capture and measure heat emanating from players as they rest on the sidelines during breaks in the game or after changes of ball possession.

The goal is to identify and help those who may be predisposed to heat illness. After intense exercise, blood flow normally increases to arteries, veins and capillaries just below the skin to help the body cool down. This mechanism is particularly active in the cheek region, one of the body’s natural radiators. Given the amount of padding worn by football players, the cheeks become a particularly important outlet for heat dissipation. Preliminary findings suggest that, after heavy exertion, players with a history of heat illness have less vascular flow to their cheeks. The researchers hope their data will pave the way to detecting heat stress in players before they suffer any ill effects, as well as serve as the basis for new tools or equipment to prevent overheating in the first place.

John Sanford is a writer in Stanford Hospital’s communications office.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.