October 5, 2011 - By John Sanford

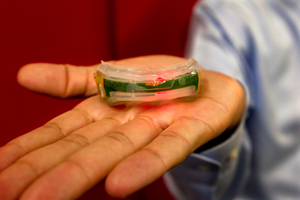

Members of Stanford's football team, as well as women's field hockey and lacrosse teams, are testing this high-tech mouthpiece to measure the brain impacts of hits they receive while playing.

Stanford University football players this season are wearing mouthpieces equipped with tiny sensors to measure the force of head impacts during games and practices.

The goal is to help medical scientists better understand what sorts of football collisions cause concussions, as well as whether there are any positions or particular plays associated with a greater risk of these traumatic brain injuries. The mouthpieces contain accelerometers and gyrometers that measure the linear and rotational force of head impacts.

Stanford is the only university in the nation using the device to collect research data from college athletes.

“This study will build toward establishing clinically relevant head-impact correlations and thresholds to allow for a better understanding of the biomechanics of brain injuries,” said Dan Garza, MD, an assistant professor of orthopaedic surgery at the Stanford School of Medicine, who is leading the investigation. “It also will serve as a helpful tool to aid in the diagnosis and subsequent management of concussions.”

The researchers also plan to collect head-impact data from the Stanford women’s field hockey and lacrosse teams, whose members soon will be outfitted with the devices.

“It’s a great opportunity for our student athletes, many of whom conduct scientific research in their academic studies, to contribute to the leading-edge research being done in sports medicine here,” said Earl Koberlein, senior associate athletic director at Stanford. “It’s a good marriage of the university’s strong academics and strong athletics.”

The study is being conducted at a time when the long-term consequences of football-related concussions have become a focus of national concern, prompting congressional hearings and new, more stringent rules on managing concussions in the National Football League. Over the past decade there has been a steady drumbeat of research correlating football collisions with chronic cognitive problems.

Dan Garza

In 2000, results of a survey of 1,090 retired NFL playerswere presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The retired players who had suffered at least one concussion during their careers reported more speech difficulties, confusion, trouble recalling recent events and headaches, among other neurologic problems, than those who had not, the survey found. That same year another study looking at the incidence of concussions among collegiate and high school players found that 888 of 17,549 had sustained at least one such injury.

Garza, who is also an emergency and sports medicine physician at Stanford Hospital & Clinics, associate director of Stanford’s Lacob Family Sports Medicine Center and medical director for the San Francisco 49ers, noted that concussions are likely underreported, given the difficulty of diagnosing them and the fact that some athletes may ignore their symptoms, knowing they will be sidelined if they speak up.

“One of the biggest problems is the uncertainty surrounding concussions,” he said. “If you tear your ACL, I can say, ‘Here’s the injury on the MRI, and here’s how we repair it.’ So there’s a confidence around treating those kinds of injuries. But diagnosing concussions is inherently subjective. Even traditional brain imaging will not pick anything up.”

High-impact blows to the head and neck are the most common cause of concussions, which also can occur when the body is violently jolted, as sometimes happens when a quarterback is unexpectedly sacked from behind.

The injury is generally understood to involve the short-term impairment of cognitive function, causing symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, headache, fatigue, sensitivity to light and noise, slurred speech and temporary amnesia.

Symptoms may not show up for hours or even days after the event. A questionnaire called the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 2 is routinely given to athletes suspected of having sustained a concussion. It asks them to score roughly two-dozen symptoms — including headache, neck pain, blurred vision, drowsiness — on a scale of 0-6. Clinicians then perform a battery of neurological tests on the athletes.

Garza plans to use these tools in combination with what will eventually be a mountain of data from the study to help establish clinically meaningful criteria for diagnosing concussions. “We need to get a better understanding of the epidemiology of these injuries,” he said. “That will involve correlating the magnitude of impacts with associated morbidities, like the number of days lost to injury, as well as looking at players’ head trauma histories to determine possible cumulative effects.”

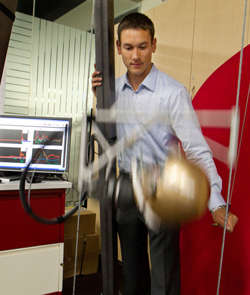

James Mattson demonstrates how the mouthpiece’s impact sensors were tested by repeatedly dropping a crash-test-dummy head outfitted with the device.

Members of the Stanford football team have been receptive to participating in the research, said Scott Anderson, head athletic trainer at the Lacob Family Sports Medicine Center. “Some of the players who are pre-med or engineering majors are especially enthusiastic,” Anderson said, though he noted that not all players have chosen to wear the mouthpieces. During games, Anderson and Jesse Free, an athletic training fellow, operate a computer on the sidelines that picks up data transmitted from the devices. Using video, the researchers also are able to correlate data to specific events on the field, such as a particular play or tackle.

To ensure the devices are measuring impacts as they would be experienced at the center of a player’s head, research assistant James Mattson, who recently earned a bachelor’s degree in human biology at Stanford, has helped to validate the device — essentially, repeatedly dropping a helmeted crash-test-dummy head that wears the mouthpiece. “We’ve dropped the head probably a few thousand times from various angles,” Mattson said.

The simulated head has other sensors planted in the middle of its “skull” to provide comparative data. “We discovered that the device measures impacts very, very accurately,” Garza said.

Although there have been previous studies of head impacts in football using sensors embedded in helmets, Garza said it is possible that the mouthpiece data will prove to be more accurate, given that helmets sometimes shift on players’ heads in a collision, which conceivably could throw off measurements. In any case, data from the study will help to illuminate the earlier findings, he said. They hope to publish their findings by the middle of 2012.

The device is manufactured by a Seattle-based company called X2 Impact, which has donated devices for the research. The study is being funded by the Stanford Department of Orthopaedic Surgery with support from Stanford Athletics. Information about the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery is available at http://ortho.stanford.edu/.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.